PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST: HEIDI LISTER HEVESY

Inspired by climbing, created by hand, our Spring 2026 prints tell a deeper story.

Tu as un compte ?

Connecte-toi pour passer à la caisse plus vite.

Add $99.00 more to quality for free Shipping!

$0.00 USD

La tournée que nous faisions ce jour-là ressemblait davantage à une mission pour explorer les options d'escalade dans la région plutôt qu’à une journée passée à chasser les virages. Nous avons skié environ 12 km (7.5 miles) sur la route du Moraine Lake et avons pris une collation rapide avant de nous lancer sur le sentier de randonnée d’été menant à Larch Valley.

Le sentier Larch Valley menant au sommet de Sentinel Pass représente 6,8 km supplémentaires (4,25 miles) avec un dénivelé de 735 m (2425 ft). Nous approchions à peine du sommet du col quand j'ai regardé en bas et aperçu une fissure qui se formait sur mon ski. Je me suis dit, c'est un mauvais signe, peut-être qu'on ne devrait pas être ici, et je me suis retourné pour discuter avec mes partenaires de la possibilité de faire demi-tour. C'est alors que j'ai vu que nous étions tous pris dans l'avalanche et j'ai réalisé qu'une grande partie de la pente sur laquelle nous nous trouvions avait fissuré, sur environ 200-225 m (650 ft-750 ft) de large, autant que je pouvais en juger à ce moment-là.

I initially tried to self-arrest, being close to the crown of the avalanche, and thought I had a chance of stopping myself or at least staying on top of the debris by slowing myself enough that the bulk of the snow would go downhill faster than me, leaving me on top.

As soon as I realized I was likely going to stop or at least be on top of the snow I started looking for my partners. The closest partner was still on top of the snow and I watched her ride the snow down almost like she was sitting in a chair. I hadn’t seen her initial struggle while also trying to self-arrest, but watched the slide carry her approximately halfway down the slope. I immediately noticed our third partner, who was around 100ft behind us, was already buried and I hoped to see some part of her re-surface so I could get a reference point while the snow was moving. Unfortunately,I didn’t see anything. I was trying to track both of them simultaneously, but I had a good idea of where the partner who was above the snow was and where she would likely end up if she did get buried. The other buried partner was more of a concern, so I paid closer attention to where I thought she was in the snow and where that mass of snow stopped. The crown spread across two aspects and the way the two slopes funneled together, along with how the slope angle changes abruptly at the bottom of the pass created a large wave that rose up like an ocean swell. It looked like she was probably underneath it. It was clear that it was a deep burial from the start, but I never expected it to be ~4m (13ft).

I wrote a more in-depth trip report about the experience in the local Canadian Rockies backcountry ski Facebook group and it was reposted by Gripped here.

Paul Clarke from the Rocky Mountain Outlook, Canmore’s newspaper, also wrote about it here.

In a quick summary, I fell from where I had self-arrested approximately 200 meters down the icy layer the avalanche slid on and ended up very close to the partner who was partially buried. We quickly checked ourselves to make sure we were ok, turned our beacons to receive and immediately headed in the direction where the wave of snow had formed. The partially buried partner was ok but still stuck in the snow buried from the legs down. However, she could get herself out so I left her and started the search.

My beacon quickly went from 35m to 20m to 12m when I heard my partner say that she had a reading closer to 9m. I immediately headed toward her and the distance on my screen started to decrease, 8m then 6m and then 4m but after that the numbers started going up again. The distance went back up to 5m and then to 6m. I backtracked, reversing back to the smallest reading and checked the other directions—the numbers all increased again, and 4m was the smallest number we saw. It seemed like she was vertically 4m below us. We were both in shock.

I had taken two AST-1 courses previously, but they were in 2004 and 2006. I don’t remember much of the details from them, but I certainly didn’t remember them covering what to do if your partner is buried deeper than the length of your probe. One thing I found, however, was the ease at which a new beacon helped me to locate the buried skier. On those avalanche courses I had taken previously I had an old analog beacon and I do remember listening to beeps and the whole process of finding a buried skier being time-consuming and not straightforward in training.

Approximately a year ago, I updated my avalanche beacon, primarily because I spend a lot of time in avalanche terrain for fun and work. It felt right to get a new beacon, as having a beacon from 2004 didn’t seem fair to either the people who cared about me or to my partners anymore. The second reason I had upgraded my beacon was because I wanted to be able to use the TX 600 which would allow me to have a secondary beacon for Trango, my dog, that I could search for on a different frequency (456hz) than traditional beacons at 457hz. I didn’t really research new beacons that much, I just knew I wanted something with three antennas and the ability to switch to a different frequency so that I could use the TX 600 transmitter as well, which limited me to the PIEPS DSP pro(redesigned as the PIEPS Pro BT).

Our memories from this part of the rescue are a bit blurred. There are moments when I don’t remember who did what, but I do remember sitting there going “F&*k she’s buried 4m … we’re f*&ked”. Fortunately, my partner had a longer probe, closer to 3m, but still our beacons were showing 4m. We quickly got our shovels and probes out, put them together and did a quick probing search. We didn’t get a strike and hadn’t expected to either, so we began the process of figuring out what to do.

The 4m reading wasn’t from standing, it was when the beacon was placed directly on the snow when we were trying to pinpoint where the buried skier was located. I quickly dug down a shovel depth and put the beacon on the snow again and it read 3.8m. I’ve been taught to test and then re-test, so I did it again, dug down another shovel depth and put the beacon on the ground, and it read 3.6m. From that, we summarized we were headed in the right direction and decided to start digging.

We knew we needed an effective area to probe so we dug down approximately a meter and created a probable area that was approximately one meter wide and 2 meters long. We didn’t do this intentionally, I think it was more instinct and logic at the time. It seemed like the right size to be able to find someone.

We probed again, and I got a strike after several attempts. It was so deep that I thought it was the ground or a boulder. I had been told previously that a probe strike would feel mushy, like a person or a coat, but that wasn’t the case. It was hard. Had we found our friend or the ground? (Turns out I had hit the upper part of her pack, I think the pack and a Tupperware case may have been what I hit making it seem more rigid then I expected).

So, we dug and dug and dug at max pace during the first 20 minutes. I had a heart rate monitor on so it’s interesting to see that graph, basically 90%+ max heart rate during those initial moments. The whole time I was cursing my small shovel … I had the smallest BD shovel at the time when I purchased it, and I was mildly upset with myself for cutting weight on one of the most important of essentials—my probe and shovel—vs leaving out an extra camera battery and other camera related stuff. There was nothing I could do about it at the time other than to make do.

When I first saw orange under the snow I was in shock again. We had found her! At the same time, I was dreading what condition she would be in. I had been involved in some other situations where I was the first responder and I wasn’t looking forward to that experience with a close friend. Then she made noise. She was alive! Next, we cleared her airway and got some snow out from around her pack, giving her room for her chest to expand so she could breathe.

We found the inReach in her pack, activated the SOS and dug her out of that hole for maybe another two hours. When digging, we initially made contact with her close to her head but her lower body and skis were still trapped in the snow. They were down another metre and farther away from us. It took longer than I thought it would to dig her out after we had freed her face and shoulder area because she was still attached to her skis. Our primary objective was to get her an airway and then deal with what came next. We knew that it would take a long time for the two of us to free her.

There are definitely a couple takeaways for me that I will apply to my future adventures in the mountains.

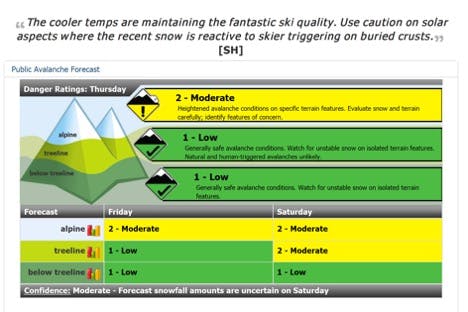

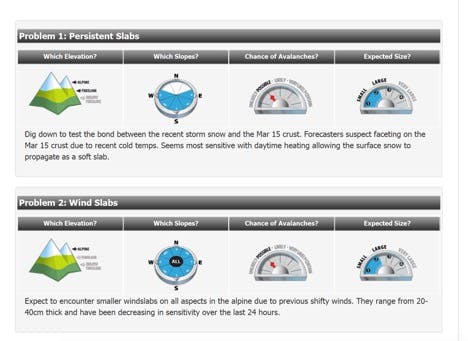

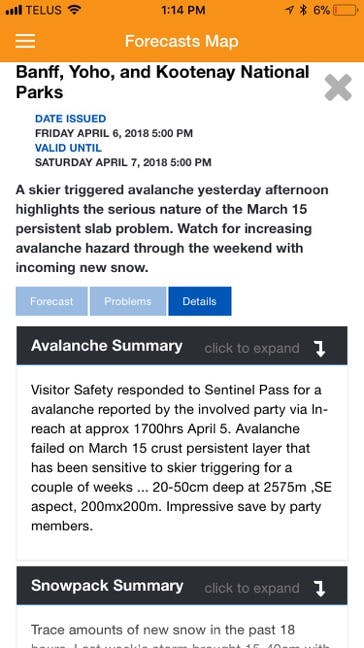

1. Read the forecast in detail. The morning of the avalanche I was rushed and did not pay particularly close attention to the bulletin. I saw Low/Low/Moderate and did not read much further. If you read the forecast from that day in more detail it discusses the possibility of triggering the layer we activated on the same aspect we were skinning up. I’d rather not get into another avalanche in the future.

Quand j'ai vu pour la première fois de l'orange sous la neige, j'ai de nouveau été choqué. Nous l'avions retrouvée ! En même temps, je redoutais l'état dans lequel elle se trouverait. J'avais déjà vécu d'autres situations où j'étais le premier intervenant, et je n'avais pas envie de revivre ça avec une amie proche. Puis, elle a fait du bruit. Elle était vivante ! Ensuite, nous avons dégagé ses voies respiratoires et retiré un peu de neige autour de son sac, lui laissant ainsi l'espace nécessaire pour que sa poitrine se dilate et qu'elle puisse respirer.

On a trouvé l'inReach dans son sac, activé le SOS et on a passé environ deux heures de plus à la sortir de ce trou. En creusant, on a d'abord atteint la zone près de sa tête, mais son bas du corps et ses skis étaient encore coincés dans la neige. Ils étaient à un mètre de plus et plus éloignés de nous. Ça nous a pris plus de temps que prévu pour la dégager après avoir libéré son visage et sa zone d'épaule, car elle était toujours attachée à ses skis. Notre objectif principal était de lui dégager les voies respiratoires, puis de gérer la suite. On savait que ça prendrait longtemps pour nous deux de la libérer.

Il y a définitivement quelques points à retenir pour moi que j'appliquerai à mes futures aventures dans les montagnes.

1. Lis la prévision en détail. Le matin de l'avalanche, j'étais pressé et je n'ai pas vraiment fait attention au bulletin. J'ai vu Low/Low/Moderate et je n'ai pas lu beaucoup plus. Si tu lis la prévision de ce jour-là plus en détail, elle évoque la possibilité de déclencher la couche que nous avions activée sur le même versant par lequel nous remontions en ski avec nos peaux. Je préférerais éviter une autre avalanche à l'avenir.

2. Il est essentiel de bien comprendre ton équipement et de savoir comment l’utiliser. Heureusement, mon nouveau beacon a fonctionné exactement comme je m’y attendais : il suffisait de l’allumer et de suivre les flèches, et j’imagine pas ce qui se serait passé si ce n'avait pas été le cas. J’aurais aussi aimé être à l’aise avec l’inReach de mon ami. En tant que passionné de technologie et gros utilisateur de gadgets, je pensais que l’utilisation d’un inReach serait simple, mais j’ai été surpris de voir qu’en situation de stress, ça paraissait compliqué. Ce n’est pas qu’il soit difficile, c’est juste que je n’arrivais pas à m’y retrouver – heureusement, mon partenaire était assez futé pour lire les instructions au dos de l’appareil et activer le SOS.

3. J'ai déjà déclaré ouvertement que je n'achèterais jamais de sonde de plus de 3 m parce que, de toute façon, personne ne vivra sous cette profondeur. Statistiquement, c'est assez vrai en considérant que les taux de survie à 2 m ne sont que de 3 %. Deux jours après notre glissade, j'ai acheté une nouvelle sonde de 320 cm. J'en ai tiré la leçon. En tant que photographe, j'ai toujours un DSLR, un objectif supplémentaire et une ou deux batteries de rechange dans mon sac, mais j'économisais sur le poids de l'équipement qui peut sauver la vie d'un ami. La prochaine fois, je n'emporterai pas la batterie supplémentaire de l'appareil photo et je prendrai plutôt la sonde plus longue.

4. Je dirais la même chose à propos de la pelle. J’ai une pelle plus grande, mais j’ai tendance à l’emmener lors de voyages qui durent toute la nuit, où je vais construire des murs de neige et creuser pas mal, plutôt que pour des missions d’une journée. Ce jour-là, j’avais une pelle plus petite pour alléger le poids. Je ne vais pas porter la petite lors de tournées similaires de sitôt. Je vais juste faire un peu plus d’efforts et emporter quelques grammes/onces de matériel en plus. À un moment donné pendant que nous creusions, nous avons brièvement échangé les pelles, et il m’est apparu que le fait d’avoir une pelle plus grande aurait pu aider lors de notre accident.

Quelques Avalanche Associations m'ont contacté et m'ont demandé ce que je pensais de l'importance de surveiller la neige à l'endroit où je pensais que le skieur enterré se trouvait, pendant que la neige glissait encore. Je pensais que c'était crucial pour notre timing pour la retrouver, car on n'avait pas vraiment de temps à perdre une fois qu'on avait commencé à chercher, et on était à moins de 10 m d'elle dans la première ou deuxième minute, car on avait une idée de l'endroit où elle était enterrée.

En 2012 étude par Pascal Haegeli de la Simon Fraser University à Vancouver, Canada, qui compare les taux de survie canadiens et suisses en fonction des temps d'enfouissement, il a été démontré qu'au Canada, à mesure que le temps d'enfouissement augmente, tu as beaucoup moins de chances de survivre à une avalanche. C'est normal, et la fenêtre de survie se situe plutôt entre 10 et 18 minutes. Pour moi, cela souligne l'importance de retrouver rapidement ton partenaire, et je pense que surveiller la neige et utiliser des balises de nouvelle génération y contribue.

Il y avait des facteurs humains qui ont conduit à notre incident, et je pense qu’en lisant attentivement la prévision, y compris tous les détails écrits, cela aurait pu changer ce qui s’est passé ce jour-là. Certainement, si je vois à nouveau Low/Low/Moderate, je ne supposerai pas que tout va bien et je prendrai le temps de lire plus en profondeur le bulletin d’avalanche.

Je pense aussi à emporter plus souvent un second appareil de communication à l'avenir. Ça pourrait faire trop de matos pour une ligne alpine légère et rapide, mais pour d'autres itinéraires, je trouve que ça peut avoir du sens. Je me dis que je peux équilibrer avec une radio VHF ou un téléphone satellite supplémentaire pour le groupe, en plus de l’inReach que quelqu’un d’autre a habituellement. Si on n'avait pas pu atteindre l’inReach du skieur enseveli, ça aurait compliqué notre journée, alors qu'on se trouvait à plusieurs heures de la route.

A couple of Avalanche Associations reached out to me and asked about what I thought the importance was of watching the snow where I thought the buried skier was while the snow was still sliding. I thought this was critical to our timing in finding her, as there wasn’t much screwing around once we started searching and we were within 10m of her in the first minute or two because we had an idea of where she was buried.

In a 2012 study by Pascal Haegeli at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, which compares Canadian to Swiss survival rates based on burial times, it was shown that in Canada, as the burial time increases you are significantly less likely to survive an avalanche. That’s expected, and the overall window of survival is closer to 10-18 minutes. To me, this stresses the importance of finding your partner fast and I believe that watching the snow and having newer generation beacons attributed to this.

There were human factors that lead to our incident, and I think fully reading the forecast, including the written details could have changed what happened that day. Certainly, if I see Low/Low/Moderate again I won’t assume that everything is fine and I will read deeper into the avalanche bulletin.

I am considering carrying a second communication device more often in the future too. That might be too much gear for a light and fast alpine route, but for other routes I can see it making sense. I figure that I can carry an extra VHF radio or sat phone for the group, in addition to the inReach that someone else normally has. If we would not have been able to get to the buried skier’s inReach, it would have complicated our day being several hours from the road.

This may not seem apparent, but don’t rush getting to the buried skier and risk getting hurt as the rescuer. Without two rescuers in our scenario, the outcome would have been different. I was able to self-arrest on the icy layer but then fell the length of the slope. Falling probably saved us time getting to the buried skier, but this easily could have gone differently. I have heard of incidents where rescuers are above the crown with buried partners far below at the base of the slope. I think chatting about not taking the additional risk of getting hurt as the rescuer and how an additional injury can create issues in the rescue is warranted; we were lucky.

Having two fit rescuers and a good understanding of what to do once the snow stopped moving helped when everything went wrong. We were fortunate to pull off such a deep companion rescue. This avalanche will change a few things I do in the mountains going forward.

--Tim Banfield

Inspired by climbing, created by hand, our Spring 2026 prints tell a deeper story.

Basic field maintenance and repair tips for your climbing skins from our Reroute team.

Watch Connor take down another classic testpiece on the Empath cliff in Kirkwood, California.

Follow BD Athlete Yannick Glatthard deep into the Swiss Alps as he shares his home...

Follow BD Athlete Yannick Glatthard deep into the Swiss Alps as he shares his home mountains with close friends.

Follow Dorian Densmore and Mya Akins for another winter season of steep Alaskan spines, backyard...

Follow Dorian Densmore and Mya Akins for another winter season of steep Alaskan spines, backyard couloirs, and deep adventures in the mountains.

Watch BD Athlete Alex Honnold throw down on some hard trad high above Tahoe.