HOW TO CHOOSE BACKCOUNTRY SKIS

Pick the best planks for your terrain of choice.

Tu as un compte ?

Connecte-toi pour passer à la caisse plus vite.

Add $99.00 more to quality for free Shipping!

$0.00 USD

Au fil des années, lors de diverses expéditions d'escalade en haute montagne, allant de la Kautz Route sur le Mt. Rainier jusqu'aux premières ascensions en Chine et au Pérou, j'ai été confronté à la nécessité de faire du rappel, alors qu'il n'y avait ni roche solide ni glace disponible. Dans ces cas, la seule option était d'utiliser une ancre à neige. Les ancres à neige demandent un brin de créativité, car tu es limité par l'équipement que tu transportes ou que tu peux trouver dans la nature, comme des pitons en aluminium, des sacs de neige, des piolets, des Bâtons de ski, des skis, des sacs à dos, des rochers et même des branches d'arbre.

Construire des ancres pour la neige est une compétence cruciale à posséder quand tu t'attaques à des itinéraires alpins techniques à travers le monde. C'est toujours un peu stressant de compter sur une corde attachée à quelque chose de bien moins « à toute épreuve » qu'une ancre rocheuse ou glacée classique, et créer une ancre de neige fiable demande bien plus que simplement s'attacher à un objet enfoui et espérer que tout se passe bien.

Maybe the most important thing to note before we get going is that snow is a highly variable medium, and thus its quality directly affects the strength of your anchor. There are countless descriptors for snow: cold smoke, powder, hot powder, mashed potatoes, corn, faceted, schmoo, isothermic, snice, rime, sastrugi, coral reef, sun cups, Cascade concrete, bulletproof, summer snowpack, and more. This is a complex subject which we will not dive into, but it is important to note that when making snow anchors, the ideal scenario is to use compact, hard, dense, and wet snow.

With that said, I like to break the process of using snow anchors down into three phases:

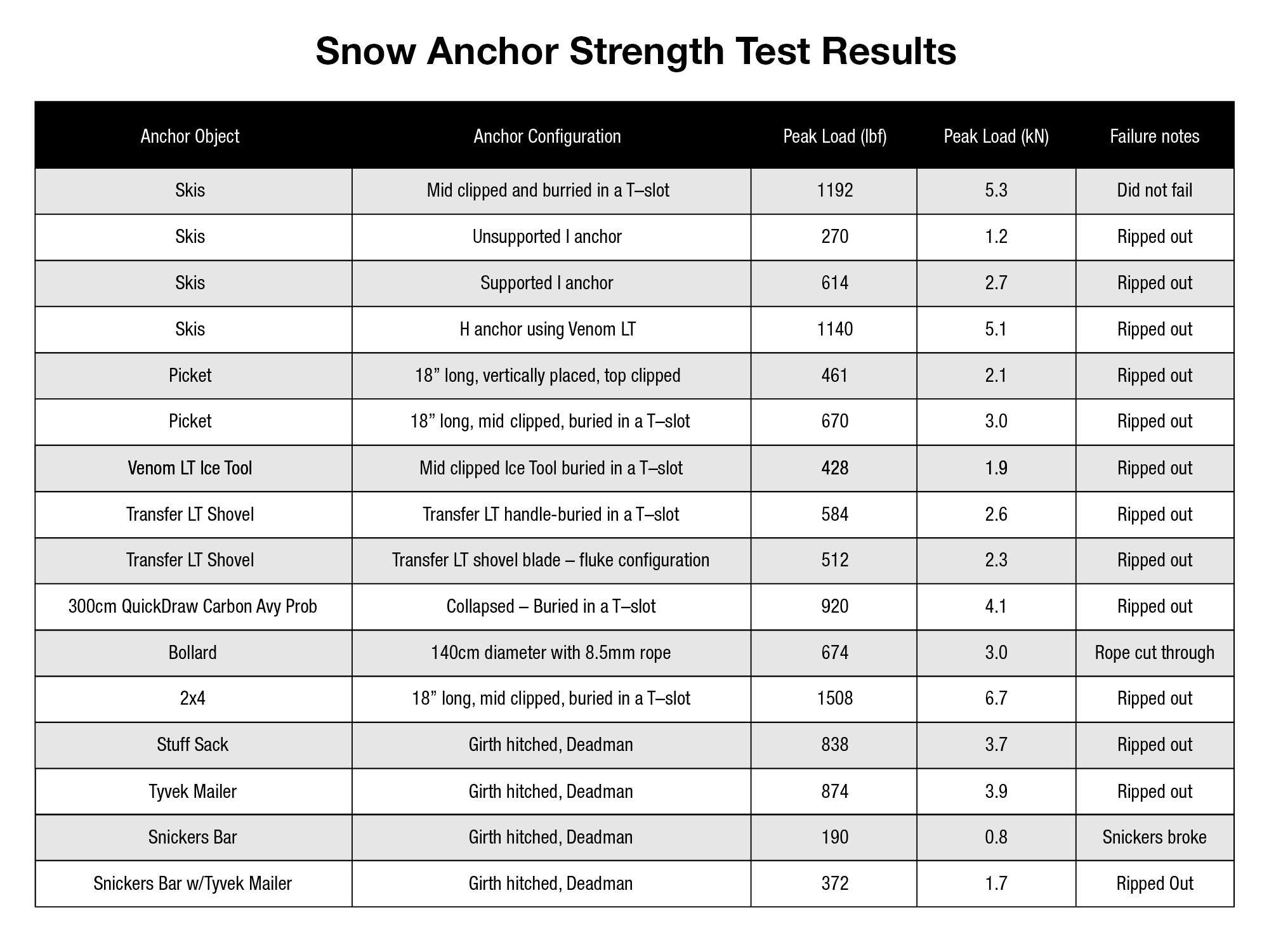

In the classic unofficial non-thesis sort of way, we headed into the Wasatch Mountains to test a variety of snow anchor configurations using a pulley system, portable load cell, and lots of muscle. This data must be taken with a grain of salt because we’re talking about n=1 here. As in ONE data point per anchor configuration in one location, on one aspect, on one slope angle, with consistent snow quality. It’s basically statistically irrelevant, but it’s always kind of cool to break stuff in the name of science.

The test setup was pretty basic: bury the test anchor object, attach the load cell directly to the anchor sling, connect a static line to the load cell, and rig the pulley system off of a tree. The test anchor was then loaded until failure or until the team couldn’t pull any harder.

We decided to focus on the most common snow anchor configurations but included a few creative ones for fun.

Les ancres les plus solides sont celles qui utilisent un objet qui maximise le contact de surface avec le mur porteur (l’avant) de la fosse. Plus l’objet a de surface pour appuyer contre la neige, mieux c’est. Un objet plus rigide, qui résiste à la flexion, répartira la charge de manière plus uniforme sur la neige lorsqu’il sera sollicité. L’objet doit être costaud. Deux skis collés ensemble valent mieux qu’un seul. Un 2x4 en pin de deux pieds de long est costaud, une barre Snickers ne l’est pas. Tu vois l’idée.

L'objet doit être enterré dans une neige dense et compacte. En général, je creuse d'au moins 12"‑20" de profondeur (30-50 cm) dans la neige compacte, je place l'objet de travers, je trace une fente fine pour la sangle d'ancrage, je rebouche le trou, puis je tasse la neige. Lire la qualité de la neige et comprendre à quel point ton objet d'ancrage est solide peut s'avérer très difficile, même pour les alpinistes les plus expérimentés. C'est pourquoi l'étape suivante est cruciale : le test de rebond.

Tu veux savoir comment construire exactement tous ces ancrages ? Je consacre un chapitre entier du MTN Sense Mountaineering Course aux tenants et aboutissants. Ici est un lien de prévisualisation temporairement gratuit.

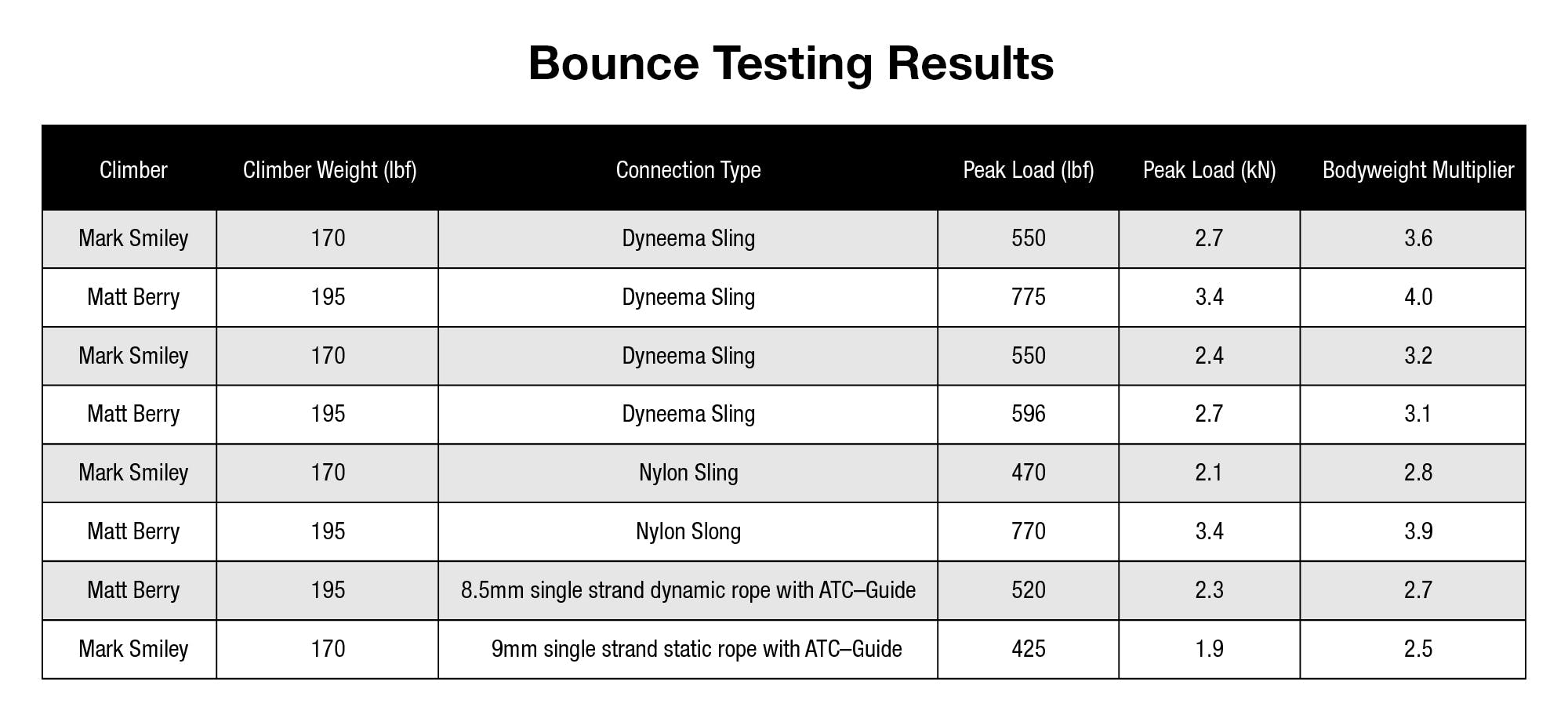

Before you commit to your newly constructed snow anchor, you should vigorously bounce test the anchor. A good bounce test should generate MORE force than the anchor will need to hold while the heaviest person is rappelling. The key is to bounce test the anchor while the anchor is backed-up. If the anchor fails the bounce test, and pulls out of the snow, the back-up anchor ensures the team remains secure. This can be achieved by building a second anchor in steep terrain. If in mellow terrain, a seated hip belay or similar may be sufficient.

Using a very static tether, like a UHMWPE sling, and the heaviest climber to perform the bounce tests, will generate the highest loads on the anchor. Aggressively throw your weight against the anchor 3 or 4 times. Watch closely to see if the snow shifts or the buried object shifts. If so, rebuild the anchor with a larger object, and/or more compact snow. Continue to monitor the anchor as the first climbers descend. When it is time for the last climber to descend, the backup anchor can be removed if the primary anchor has been deemed “strong enough”.

Après avoir testé les ancrages de neige sur le terrain, nous étions curieux de savoir combien de charge pouvait être générée lors d'un test de rebond, alors nous sommes retournés au labo QA pour prendre quelques mesures. Un ancrage a été fabriqué à l'aide d'une sangle UHMWPE enroulée autour d'une poutre en I en acier, une cellule de charge a été fixée à l'ancrage, on s'est attaché à celui-ci et on s'est lancé. Les résultats représentent le scénario optimal dans lequel les charges les plus élevées peuvent être générées lors d'un test de rebond.

Les données que nous avons recueillies ont remis en question mon hypothèse précédente selon laquelle le test de rebond avec une élingue en UHMWPE exerce des forces MASSIVES sur l'ancre. Ce n'est vraiment pas le cas. Il faut vraiment marteler l'ancre pour générer une force supérieure à celle qui peut potentiellement être générée lors d'un long rappel saccadé. Cependant, l'utilisation d'une élingue en UHMWPE génère des charges bien plus élevées que le test de rebond lorsqu'elle est montée pour le rappel avec une corde et un ATC.

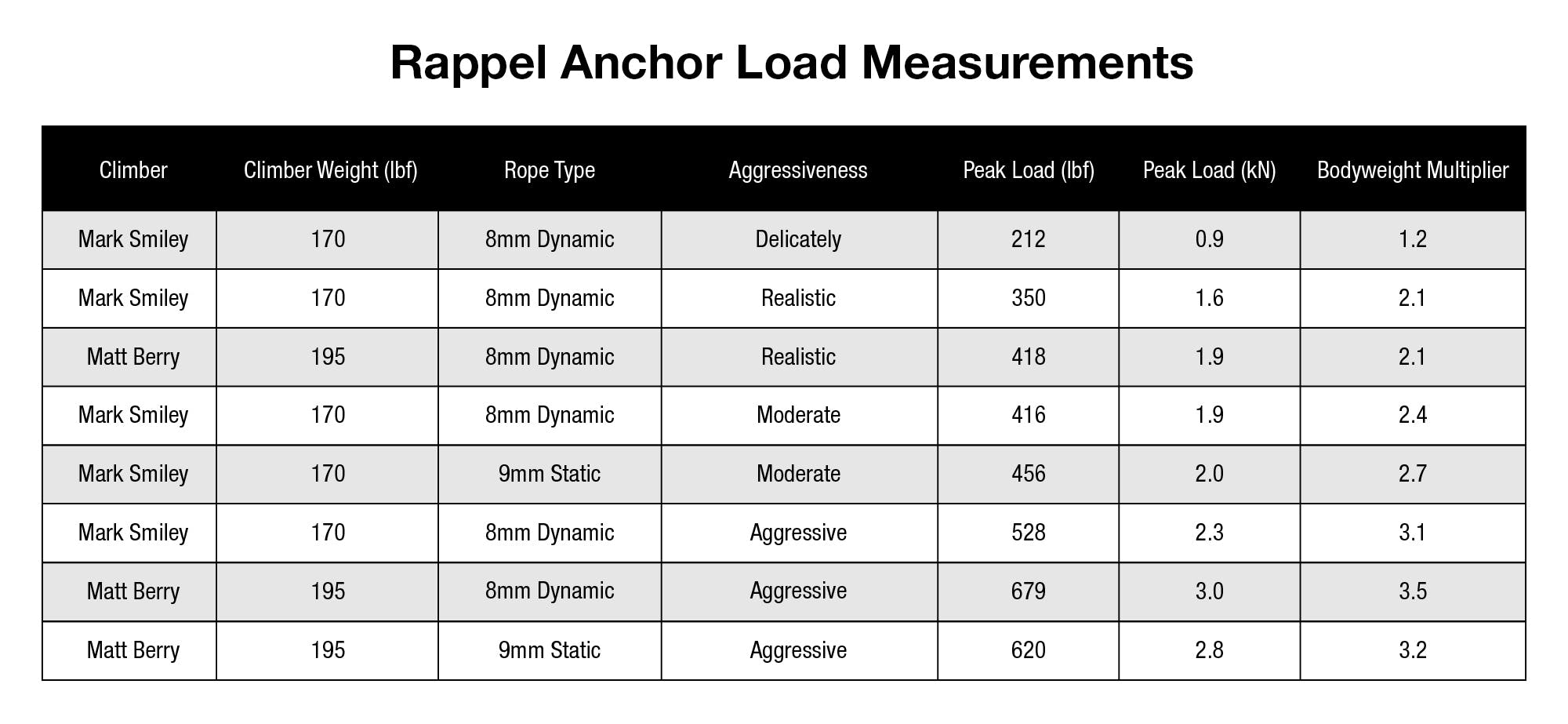

Now that you’ve finished bounce testing and are happy with the results, it’s time to commit to the anchor. When rappelling, slow is smooth and smooth is safe. In this case, a smooth rappel reduces the chances of shock loading the anchor. If you let the rope run through the device quickly, and then brake abruptly, this can generate more than 3X your bodyweight on the anchor! That is extremely concerning when you consider the difficulty of generating equivalent loads while bounce testing. We want to apply the least amount of force on snow anchors as possible when rappelling.

A series of 30-foot-long, free-hanging rappels were made to measure how much force is generated at the anchor. A combination of static and dynamic ropes was used during testing and to our surprise there wasn’t a huge difference. It is possible that the difference between these two rope types would become more significant on longer rappels.

Prior to these tests, I thought that even during a steep pitch, if I rappelled really smoothly the anchor would only need to hold my bodyweight. After looking at the data, the results indicate that the anchor needs to hold at least 1.2X my bodyweight during an extremely smooth rappel or 3.5X my bodyweight in a jerky free-hanging rappel at this height.

If we consider an 80 kg (176 lbs) climber is capable of generating 3X their bodyweight on a jerky rappel, we need an anchor that is at least capable of holding roughly 2.5 kN (562 lbs). And that’s with NO BUFFER! Looking back at the strength of the snow anchors that were tested in the field, only 10 of the 16 test configurations would meet this requirement, two of which would be extremely borderline. A proper bounce test would have been capable of identifying most of these sketchy anchors.

Some rules of thumb that we should keep in mind when building any type of anchor:

- You can generate 3 – 4X bodyweight when bounce testing using a UHMWPE tether.

- An aggressive, jerky, rappel can generate more than 3X bodyweight whereas a smooth free-hanging rappel could be as low as 1.2X bodyweight.

The lesson here is that you must be aggressive when bounce testing and use a very static tether to generate loads high enough to properly ensure the robustness of your anchor. Otherwise, a jerky rappel may result in higher loads than you can generate with bounce testing.

In the end, we need to build the strongest anchor possible, vigorously bounce test the anchor with a backup anchor in place, and then delicately rappel.

For further reading, see video on snow anchor testing conducted by ENSA and this white paper.

Stay safe out there!

Inspired by climbing, created by hand, our Spring 2026 prints tell a deeper story.

Basic field maintenance and repair tips for your climbing skins from our Reroute team.

Watch Connor take down another classic testpiece on the Empath cliff in Kirkwood, California.

Follow BD Athlete Yannick Glatthard deep into the Swiss Alps as he shares his home...

Follow BD Athlete Yannick Glatthard deep into the Swiss Alps as he shares his home mountains with close friends.

Follow Dorian Densmore and Mya Akins for another winter season of steep Alaskan spines, backyard...

Follow Dorian Densmore and Mya Akins for another winter season of steep Alaskan spines, backyard couloirs, and deep adventures in the mountains.

Watch BD Athlete Alex Honnold throw down on some hard trad high above Tahoe.